Our

Treasury seems wedded to the idea of a tax on carbon emissions. In this, they are cheered on by the

Department of Environmental Affairs, but the Department of Energy and the

Department of Public Enterprises both seem to be having some reservations. If

it is proving difficult to finance Eskom, and economically undesirable to hike

the cost of power any more, why would we want to increase the power cost yet

further in the vain hope of saving the planet?

It all goes

back to that proud moment in November 2009, when our State President stood

before the world at a gathering in Copenhagen. He offered to reduce our carbon

emissions by large amounts provided the developed nations would help with the

costs of the reductions. At the time, it

was seen as a noble gesture on our part.

Now, the gilt has fallen from the offer, not least because the

anticipated help has been conspicuous by its absence. The developed nations have come face-to-face

with the economic downturn. Saving the planet has moved lower on the list of

priorities.

There are

three major things wrong with the tax idea.

First, the plan announced by President Zuma wasn’t a plan in the first

place. What he said was:

With financial and technological support from developed countries,

South Africa for example will be able to reduce emissions by 34% below

‘business as usual’ levels by 2020 and by 42% by 2025.

This was a

scenario from the Long Term Mitigation Scenarios, which was called “Required by

Science.” Now scenarios are not plans, they are sketches of what might be

possible. Moreover, science does not

require anything; it merely provides a platform for understanding. But the Department of Environmental Affairs

sprang upon the scenario with glee, believing in their zeal that science really

had produced a plan out of some magic hat.

With no further thought of the implications of what they were doing,

they set about trying to implement something that had every chance of not being

possible. The carbon tax is part of their plan of implementation.

The second

thing wrong with it is that it is an economic disaster. Treasury evaluated the impact, and found it

made the rich richer and impoverished the poor. Indeed, the impact was hardest

on the poorest. To understand why it is a disaster, you need to recognize that

there is a very strong relationship between economic growth and the consumption

of energy. To grow the economy, you have

to provide more energy. But over 90% of South Africa’s energy comes from fossil

fuels. Most of our energy gives rise to carbon dioxide emissions. So economic growth means more energy which

means more emissions.

It is

possible to reduce the linkage between economic growth and energy consumption,

but this cannot happen overnight.

Nowhere in the world has there been delinkage at the rate that the Long

Term Mitigation Scenarios would require – and, note well, the scenarios were

long-term to begin with.

It is also

possible to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels. Indeed, this is precisely what the Department

of Energy’s renewable power programme is designed to do. But even the latest Integrated Resource Plan

Update would not produce the sort of drop in reliance that the Mitigation

Scenario would require.

The

Department of Environmental Affairs recognizes these problems, so it has come

up with a different plan. It aims to set

up a carbon trading platform, which will allow companies that produce carbon in

excess of some arbitrary limit (which the Department will set) to buy emission

credits from companies which produce less carbon than the limit. Treasury, advised by a group of would-be

carbon traders, has agreed to this ploy.

There are

at least three objections – on Treasury’s own calculations, there is

insufficient volume of tradable carbon to support such a scheme; a few

industries which have found ways to save carbon have already cashed in on the

various pre-existing schemes such as the Clean Development Mechanism; and, most

damning of all, it would establish a bureaucracy within the Department of

Environmental Affairs which could control emissions and thereby the entire

economy at the merest whim. The fact that carbon trading platforms have been a

disaster in the US and have cost the European Union billions in ineffective

support (and lost VAT) has not been sufficient to persuade either the

Department or Treasury that such a scheme is ill-advised. Treasury is doubly

culpable in this – the foxy carbon traders showed it how to design a carbon

henhouse, a sure-fire way to lose the chickens!

The third

thing wrong with a carbon tax is that it would achieve nothing. There seems to be some sort of zeal in our

Government to save the world from a possible carbon hell. South Africa emits around 1% of global

emissions. Suppose we were to reduce our

emissions by a quarter, which would probably wreck our economy for good, the

global impact would be absolutely nil.

It might be

justified if the rest of the world had similar zeal, but it demonstrably has

not. The Kyoto Protocol came into effect

in 2005. In the first commitment period, 2008-12, many developed

countries agreed to legally binding limits on their emissions. What happened?

Well, between 2008 and 2012, global fossil fuel use went up by 8.5%, and the

contribution of fossil fuels to global primary energy supply was unchanged at

87%. Is it worthwhile committing

economic suicide to protest the failure of others to observe legally binding

limits?

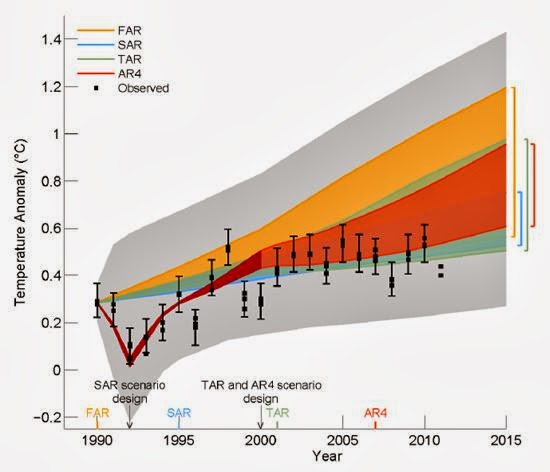

Moreover, with every passing year the whole rationale for

reducing carbon emissions is becoming weaker and weaker. In the past 16 years, emissions have gone up

40%; global temperatures have been stationary.

Indeed, there has been only a short period in our history when the

hypothesis that carbon emissions and global temperatures are linked was

supportable. That was between 1970 and 1997. Before then, the world cooled as

emissions increased, and since then the temperature has not changed.

Instead, a different hypothesis has emerged. This proposes

that there will be more extreme weather in a warmer world. However, it is not demonstrable. To the contrary, it has been possible to

extend many measures back to the late 1800’s. We can now see how extreme the weather

was in earlier times. Even though the

world has demonstrably warmed over the past 150 years, there has been no detectable

change in the frequency or severity of extreme events. One of the surprises has been that the world

has not become measurably wetter, which seemed very likely in a warmer world.

So the rationale behind a carbon tax is now very weak. It always was weak. The idea that a tax will encourage a change

in social behaviour is seductive, but a little thought will soon show the

flaws. It was long hoped, for instance,

that swingeing taxes on tobacco would reduce smoking, but it had little effect.

Other laws became necessary to bring about the desired social change. Alcohol consumption continues unabated – the

annual increase in the sin tax has an imperceptible effect. At least with tobacco and alcohol, it is

possible to cut down on consumption.

Carbon, with its direct linkage to energy and wealth creation, can only

be cut back by greater efficiency. Most large users of energy have already done

much to improve their efficiency as far as possible. Further improvement is up against the law of

diminishing returns.

Carbon emissions are therefore inelastic, in economic terms.

Adding a cost to energy has an impact on the demand by closing otherwise

profitable industries. Jobs are then lost.

It is happening in our economy right now. That is ultimately the reason

why there are no grounds for taxing carbon.